In contrast to the previous chapter, this next chapter was one of the easiest chapters to write. Very little changed from the original draft to the published version.

When I say very little changed, I don’t mean that in terms of actual count of words added, deleted, and moved around. I’m more referring to the significance of the revisions.

Since there were no significant revisions for this chapter, it is probably a good place to discuss how I do revisions generally, and what happens between typing “THE END” on the first draft to hitting “PUBLISH”. That’s because you can get a clearer picture of the extent of revisions that happen when there are no structural issues present.

(Structural issues, like those in Chapter 3, generally require extensive rewrites so I basically treat them as writing new prose.)

Scoping revisions

Typically, I divide revisions into two categories: major and minor revisions.

Anything that changes the overall shape of the story qualifies as a major revision. Adding, deleting, or moving scenes around are major revisions. Anything that impacts the overall tone, plot, and character promises of the story—like rewriting a scene from a different perspective, or from the same perspective but with a different emotional tone or arc—is also an example of a major revision. Big stuff that often, but not always, affects more than one scene or one chapter.

Minor revisions are similar in nature, but instead of working at the arc/chapter/scene level, I’m working with paragraphs, sentences, and individual words. That is, the scope of the revisions are contained within a single scene.

When I write new prose, I generally write every scene in a given storyline in sequence. I think (though I’m not 100% certain since I don’t feel qualified to attempt something as difficult as this) that if I were to utilize a narrative structure where there are flashback sequences, I would probably treat each timeline as a distinct storyline and write each of them in sequence. There’s an upfront time cost for me to get into the right headspace for the plot and the characters involved, so it’s easier for me to stick to one storyline at a time. Bouncing around different POVs in the same storyline doesn’t matter as much.

(This is what Brandon Sanderson does when he has to juggle complex multiple storylines; he writes each “throughline” from the beginning to the end and then interleaves the chapters together later. Here’s an example from The Lost Metal on how it works.)

But when I’m writing any given scene, even though I try to write the scene from beginning to end, I do jump around within the scene. I’ll write bits of sentences that I like the sound/feel of, but it won’t quite fit in with the natural flow of the prose that has gone before, so I’ll stick all of these orphaned phrases at the bottom of the document while I do my best to forge on, until I find the right place in the flow to slot them in.

Whatever doesn’t make it into the scene gets moved into the prose graveyard. RIP. If you’re curious, I ended up with 17,179 words in the prose graveyard by the time I was finished with major revisions on Petition, and an entire deleted prologue that was 5,856 words long.

Alpha and beta feedback and revisions

This is the most important stage of revisions for me. I don’t currently use a developmental editor for two reasons: first, because it wouldn’t be commercially viable at the moment; and secondly, because I’m fairly confident in my ability to spot structural issues in narratives, based on my writing experience.

Even so, I do not publish anything until it has gone through both alpha and beta readers. I rely on them heavily to gauge whether or not scenes are landing emotionally the way I intend them to, whether I have alignment between my promises and my pay-offs, the pacing of how my plot/characters progress, and whether things make sense from a continuity and world-building perspective.

My rule of thumb for whether or not I act on alpha/beta reader feedback goes something like this:

- Only 1 reader pointed it out = I’ll action it if I agree with it

- 2-3 readers remark on the same thing (could be agreement or disagreement) = I need to investigate the issue and give it serious thought. 7 or 8 times out of 10 though, the feedback is either correct or points to a deeper issue and I’ll address it

- More than 3 readers have an issue = this is a critical flaw I need to fix

Early readers were divided on the first scene. Some found Rahelu’s introspection slow; some enjoyed the change in pace and the description of the scenery; some had a problem with Rahelu’s run-in with her mother, citing their dislike of using miscommunication as a source of that conflict/tension.

Feedback on the second scene, however, was unanimous: the best chapter so far. Everybody liked the dynamic between Keshwar and Tsenjhe, and their interactions with Rahelu. Phew! No changes needed here.

The issue with pacing in the first scene was minor, and something that I knew could be addressed during line edits, which I’ll discuss below. The bigger issue to consider at this stage was whether or not I wanted to keep the nature of the conflict between Rahelu and her mother.

The Tiger/Asian Mom is a well-known and well-caricatured stereotype these days, to the point where it’s often just used for cheap humor. But that stereotype is rooted in truth, and that painful truth is, miscommunication and misunderstanding is a huge part of many immigrant parent/child relationships in my experience.

It is one of those things that sounds incredible silly to a third party observer when summarized, but when you live that experience, it is the kind of thing that tears you up from the inside and breaks you down, no matter how old you are.

For better or for worse, this kind of family dynamic is representative of the immigrant story I was trying to tell, so I felt it was important that Rahelu’s relationship with her mother reflected this consistently. Thus, I decided to leave the first scene as written.

Line edits

I do line edits in two stages.

World building pass

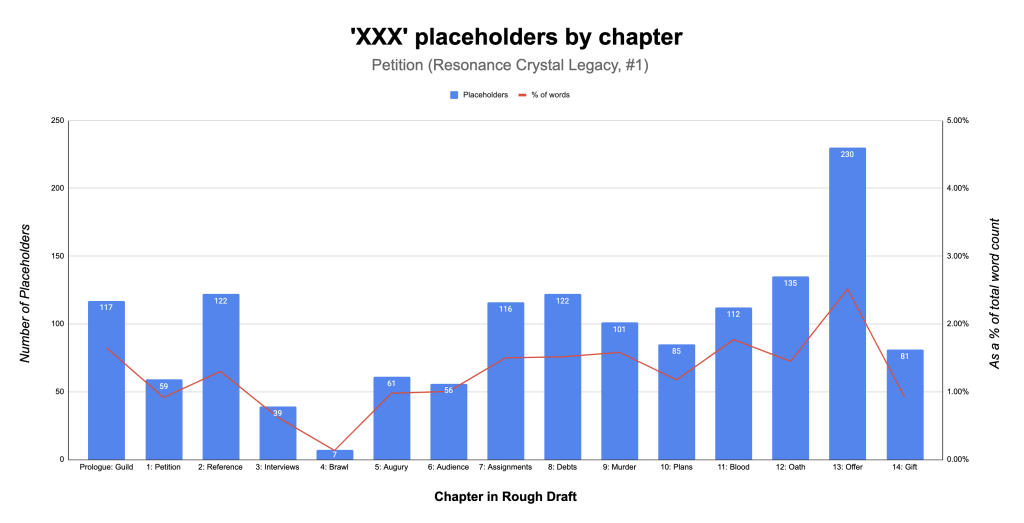

This is where I fill in all of the ‘XXX’ placeholders in my manuscript.

When I write new prose, I do everything I can to focus on getting the plot and character arc down on the page right, and to avoid getting caught up on stuff that I know I’m going to fix later.

That means putting an ‘XXX’ placeholder in whenever any of the following things happen:

- I can’t think of the right word or phrase I want to use in that specific part of the prose: this could be for the way it sounds, what it means, an how the word or phrase visually looks on the page, or even just that rhythmically an additional word or phrase that I can’t think of would be more pleasing to the ear, etc.

- I haven’t named a character or location or an in-world term. There were a lot of ‘XXX’s at one point for all the swearing, when I was debating if I should use invented fantasy swears. Believe it or not, Keshwar was the reason that I decided to go with real world curse words—mainly because one of his lines in the next chapter just doesn’t sound right without them.

- I need to quantify something (amount of time, timeline, distance, number of objects/people, money) and I haven’t decided exactly how many is feasible or reasonable in the scenario. Yes, I have a spreadsheet that calculates the loan amortization schedules for Rahelu’s family’s fishing sloop and her Guild debt, as well as list of every good or service that appears on the page and is paid for by a character, and a weekly budget listing income and expenses for Rahelu’s family.

- I need a technical detail that I haven’t researched. If you’re curious, a lot of this had to do with fishing and the commercial sale of live seafood when refrigeration isn’t commonly available.

- I need a sensory detail that isn’t plot critical. Honestly, a lot of this is clothes and food.

- I need a specific resonance detail. Since colors and textures have significance here, I need to make sure I’m using them in a consistent way. This is my version of Sanderson’s revision pass to add spren into the Stormlight Archive books.

I’ve tried writing without placeholders before and it utterly destroys my efficiency. Here’s an accurate summary from Ursula Vernon:

All told, there were 1,443 ‘XXX’ placeholders that needed to be eliminated for Petition:

It took me a month to get rid of them all.

Prose

Here are all the different kinds of line level edits I do, to make the prose as polished as I can:

- Continuity: these mainly related to the way the sequence with Xyuth in the Tattered Quill unfolded after structural revisions, as well as eliminating references to a recent interaction with Onneja. That was a scene that originally took place in between Rahelu and her mother arriving at the market and Rahelu lining up to hand in her Petition at the Guild. We’ll talk more about it when we get to Chapter 13.

- Character details: Rahelu’s habitual resonance ward is something that comes up throughout the book that is thematically important to her and how the book ends. I’d made sure to mention it a few times throughout but I still did have some beta readers who were a little confused by it at the end, so I took the opportunity to reinforce it here.

- Emotional distance: I have a natural tendency to write in a distant third personal limited perspective. I suspect it’s because I focus so much on pinning down specific, observable things when I draft scenes. When I’m across the viewpoint character’s frame of mind and in a flow state, it’s easier for me to write prose that’s more emotive/evocative, but this is rare. Generally, I have to work hard to reduce the distance in my perspectives.

- Flow: this has to do with the narrative arc of the prose and the rhythm of how it reads:

- I try to nest arcs within arcs within arcs, so that each word forms an arc in a sentence, sentences form an arc in a paragraph, paragraphs form an arc in a scene, and scenes form an arc in the chapter, and the chapters form an arc in the book.

- Often, this involves me doing things like: moving sentences around until I’m happy with the order in which ideas are presented; sitting there changing my mind ten times about where I want to put line breaks; debating whether I want to have a long, half-page sentence with twenty clauses in it or whether it should be split up and if I split it up, how I want to punctuate it.

- Sometimes, this involves me making a slight change at the end of the chapter by adding a hook. I have a natural tendency to end chapters right at the point of emotional impact. This generally works in later chapters because by then you’re invested enough in the characters and the story to keep reading to the end. Not so great in the early chapters because it doesn’t compel a page turn, thus allowing a clean exit point to stop reading.

- Pacing: I tend to overwrite narration and description on my first drafts, since I need it to get into the viewpoint character’s head and to envision the space they are in. Most of the time when a scene drags, I can fix it by cutting back on the narration.

- Word choice and phrasing: this is where I try to make a character’s voice more distinct. Examples include: deleting (excessive) filler words, replacing adverbs and adjectives with stronger verbs and more specific nouns, eliminating anachronistic or overused words or phrases, eliminating the repetitious use of words and phrases in close proximity, etc.

Extensive line edits tend to involve me addressing comments that past me left on the manuscript while I was writing the first draft. (Those mostly consist of things like: “this line sucks”, “UGH this is SUPER LAME”, “maybe this? or that? IDK”, and “fix this later”.) Sometimes, my alpha and beta readers will have left line level comments as well—this doesn’t happen often, because it’s not their focus, but they will mark things up if it sticks out to them. If so, this is when I look at those comments.

The rest of the line edits I tend to do in conjunction with copyedits—see below.

Copyedits

Once line edits are done, I export my manuscript from Google Docs and put it into Vellum for typesetting and book formatting. By this stage, any further changes that need to be made generally involves punctuation and are not extensive.

(There is an argument to be made that I should keep my manuscript in Google Docs until the very last moment. But doing that means a big time crunch when it comes to getting cover art finalized and the book uploaded for publication, which is why I stop working in Google Docs after line edits.)

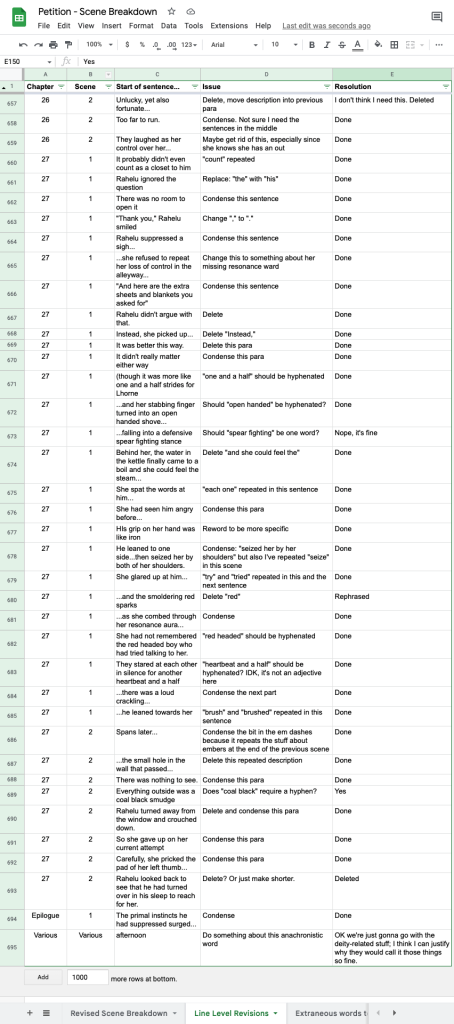

Next, I do a complete read through of the manuscript and scope my line edits. This involves logging every single thing that bugs me at the sentence level in a spreadsheet, including anything that I’m unsure of:

This is the hardest part of the revision process for me. I can’t afford a copyeditor yet, so I am reliant on tools like Hemingway and Grammarly. I don’t always take all of the suggestions, but I do investigate all of the issues that are flagged.

A lot of the changes at this stage have to do with hyphens, commas, and US English. I made a conscious decision to write in US English even though I am Australian, simply because the majority of my readers are based in the US, and those who aren’t are used to reading in all forms of English.

Still, I had to draw the line on some things. Example: I don’t care if “leaped” is common than “leapt” in American English; I prefer the sound of “leapt” and it’s not wrong, so I’m keeping it.

Proofreading

This is the most tedious and agonizing stage. It involves me sitting with the printer files and reading the entire book backwards.

Yes, backwards.

As in, I start on the last word of the last page and read the whole thing backwards, word by word. It does my head in like nothing else.

But it absolutely works, because I pick up errors that have been there since the first draft and have gone unnoticed the whole time because everybody was autocorrecting it as they read it.

(Apparently two other effective tricks are to read it aloud and change the font to Comic Sans. I may try that for Book 2, since there was still an error that slipped through despite my best efforts. And if you spot something that might be an error, you can report it here.)

Upload

Once proofreading is done, I upload the print-ready PDF files and the EPUB files. It can take anywhere from a few minutes to a few days for me to get a proof file.

Checking the proof file is usually a quick process of doing a page flip to make sure nothing is weirdly formatted or cut-off.

If I see any errors, I correct them in Vellum, re-upload then recheck the proofs.

Publish

Once I’m happy with the proofs, I approve the files for publication.

Here’s a tracked changes version of this chapter from original draft to the final published version, so you can see exactly what changed. (And if we’re counting out of curiosity, then there were 196 changes in total, according to Google Docs.)

Leave a Reply